It was 1987.

It was the era when we wore large square glasses, and we watched the (original) A-Team on TV. Phones with buttons were the newest rage, and began replacing the old round-dial type phones. These were modern times indeed.

I was in Windhoek High School, one of the largest and most prominent schools in the country, with a proud history of achievement and success. I wasn’t old enough to vote yet, but the government already had it’s eyes on me since I was 16. They sent me a letter in my 16th year, confirming that I was due to report for duty as soon as I left school. (This was enough motivation for most kids to actually finish school and not leave at the age of 16…)

Since we were 12 years old, in what we called “standard 5”, (our first year of high school), we had to wear brown cadet uniforms once a week. Every Wednesday morning we had to line up for parade, and we were taught how to march in threes and salute the officers, who were also doubling as our teachers.

During the first week at high school, we were provided with a brown shirt, brown shorts, and a brown beret. This was to be worn every Wednesday, and you were in serious trouble if you turned up at school on a Wednesday wearing your normal school uniform. “Serious trouble” normally included some form of physical punishment – at least two strikes in the office to be exact. We all accepted this as a fact of life, and our parents wouldn’t even consider complaining about the fact that their little beauties were beaten at school because they did not present themselves in proper military attire.

We also had regular hair-inspections in school, and were unceremoniously taken to the office if our hair standards did not comply with school regulations.

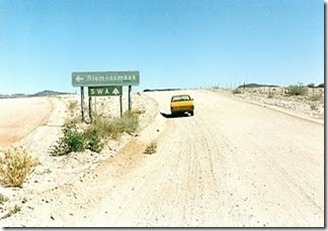

You might think that I was in a private military school, but you would be wrong. This was a normal state school in SWA.

This was the way we were raised, and we all accepted this without thinking twice about it. Our whole way of life was based on survival and fighting for our freedom and our country. Those who questioned this, were frowned upon. (And probably beaten up during recess)

When we went on road trips during the school holidays, we were used to seeing long army convoys on the road – just another one of those facts of life which we endured because we knew these convoys were crucial to our survival. They were delivering logistic support and backup to the troops up North. They slowed down our progress on the long narrow roads of SWA, but they also gave us the assurance that someone was out there protecting us.

I grew up seeing uniformed people everywhere I went, and thought this was quite normal. Windhoek was squirming with military personnel, and even my own dad worked for the army. The yearly Windhoek Agricultural Show was heavily sponsored and dominated by the army. We could see the newest weaponry, and the SWASPES special forces would do shows on the showgrounds where they performed mock attacks on terrorists.

We enjoyed watching the motorbikes do tricks, shooting at targets while flying through the air, and the dogs attacking make-believe terrorists who were hiding in the crowd. They would have smoke all over the grounds and “donderbuis” bombs going off – great stuff to watch from the stands! The baddies would shoot at our soldiers and they would shoot back, killing the enemy in droves.

Ahh, what a joyful time it was indeed. I often dreamt of killing a terrorist myself one day.

There were helicopters and sometimes even Mirage fighters flying overhead, all of them displaying the might and pride of the South African Defence Forces.

Although the war was waged far away in the North of our country, we were all very much aware of it, and accepted it as a normal part of life. We were South Africa’s 5th province – we had the same Orange, White and Blue flag, and we sang the same national anthem with the same pride.

By our final school year, which we called “Matric”, or Standard 10, the young men all had to make some serious decisions. We received another blue computer-printed notice in an envelope. All of us got one – no one was spared.

In this little blue note, you were informed that you were expected to turn up at Suiderhof Military Base on 11 January 1988. It wasn’t a nice Outlook meeting request or a friendly letter, it was more like a stern command. The only way out was if you applied to go to university after school, but this was just a way of delaying the inevitable.

I tried to convince my parents that it would be better for me if I went to Stellenbosch to start my engineering studies – I’ll deal with the army later. My parents did not agree, and made me “volunteer” to join the army after school. According to them this would be better for me in the long run, because I might get married at University and the army experience is even worse for married men. “Get it over with and enjoy the rest of your life”, is basically what they prescribed.

Long story short: this decision was made swiftly and without further discussion – I was going to the army and that was that.

Once the matter was settled, those of us who made the decision to fight for God and country were revving up each other. We were animatedly discussing how brave we were and how many terrs we were going to kill, taking Caspirs for spins in the white Wamboland sand, jumping from helicopters and throwing around hand grenades all over the place. The army would never be the same after this lot enlisted…

In those days we did not yet have the luxury of the internet where you could research stuff at the click of a mouse. All we had to go on were the stories of the legends, and the stories that were told by those who went before us.

That is, if they said anything at all. Men will always tell about the fun stuff, and the funny stuff, but you don’t often hear about the killing and the fear and the hurt of losing a comrade in battle. Or the feeling of betrayal once it’s all over and people call you a baby killer or an evil racist.

Other than that, we had the propaganda and the embedded fear that these animals will run over our border and destroy our country – enough to make you want to go and massacre the lot of them.

There were all sorts of stories, but none of them unleashed the fear that the word “Osona” unleashed. This was the name of the Military school at Okahandja, also known as 1 SWAMIL.

Osona was where all the Southwest-African kids went for military training, and it was known as a place where kids died and young men were born overnight. There were horrible rumours about a terrible sergeant major who marched a soldier till he literally dropped dead, and about a torturous event called “Vasbyt”. This was where big men cried and the big brown army machine showed no mercy. This was where we were all destined to go – an infantry training school like none other. A place where canon-fodder was prepared before unleashing it to the unsuspecting enemy.

1 SWA Military school, Okahandja. The base is still there today, albeit in a much worse state than it was ever imagined to be during our days.

One Monday morning during our last weeks in school, we were all called up to the stage during assembly. The whole school could have a look at us and see the men who were destined to die for their country. We felt really good – all the girls were checking out the brave young lads who were risking their very lives to protect them. We were the ones fighting against the evil forces of the communists and the antichrist. (Yep, those were the exact words.) You can still see the photo in the back of our yearbook of 1987 – all of us standing there, ready to take on those commie bastards.

It felt great. For a while, anyway.

I had a look around, to get an idea of who my buddies were. It was good to see I wasn’t going to be alone – some of these idiots would have to endure Osona and Vasbyt with me, and this just made everything so much easier.

We were ready – as ready as anyone could have been. But the future turned out way different than any of us had ever imagined back then. And it changed quite suddenly, too.

I’ll tell you more about this in Part 3…

Read Part 3